Introduction – what motivated the Balfour Declaration? (Powerpoint of Key Players)

Introduction – what motivated the Balfour Declaration? (Powerpoint of Key Players)

There is still conflict as to which motive for the Balfour Declaration is stronger – there are at least three motives, and some may interlock:

1. According to Avi Shlaim, there are two main schools of thought:

He cites Leonard Stein’s[2] conclusion is that it was the activity and skill of the Zionists, and in particular Dr Chaim Weizmann, the remarkable Belarus-born chemist who would become the first President of Israel), that induced Britain to issue the letter addressed to Lord Rothschild. (We return to Weizmann). Others would put the emphasis more on the Christian Zionist element in the Cabinet.

According to Mayir Verete (‘The Balfour Declaration and its Makers’, Middle Eastern Studies, 6 (1), January 1970) the letter was the work of hard-headed pragmatists, primarily motivated by British imperial interests in the Middle East – it was the desire to exclude France from Palestine, rather than any sympathy for the Zionist cause.

David Fromkin supports the imperialist interests motif:

As of 1917, Palestine was the key missing link that could join together the parts of the British Empire so that they could form a continuous chain from the Atlantic to the middle of the Pacific.[3]Moreover, the British thought a declaration favourable to the ideals of Zionism was likely to enlist the support of the Jews of America and Russia for the war effort against Germany. In contrast to Stein, Verete concludes that Zionist lobbying played a negligible part in the process.

2. Tom Segev in his book on the British Mandate in Palestine (One Palestine: Complete, London, 2000) provides another interpretation – namely, the prime movers behind the letter were neither the Zionist leaders nor the British imperial planners, but Prime Minister David Lloyd George, whose support for Zionism, he argues, was based not on British interests, but on ignorance and prejudice.

Segev concludes: the British entered Palestine to defeat the Turks; they stayed there to keep it from the French; and they gave it to the Zionists because they loved ‘the Jews’ even as they loathed them, at once admiring and despising them. Thus the Declaration

was the product of neither military nor diplomatic interests but of prejudice, faith and sleight of hand. The men who sired it were Christian and Zionist and, in many cases, anti-Semitic. They believed the Jews controlled the world. [4]

3. A further motive– the American dimension: James Gelvin, a Middle East history professor, claims that issuing the Balfour Declaration would appeal to President Woodrow Wilson’s two closest advisors, who were Zionists.”The British did not know quite what to make of President Woodrow Wilson and his conviction (before America’s entrance into the war) that the way to end hostilities was for both sides to accept “peace without victory.” Two of Wilson’s closest advisors, Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, were avid Zionists. How better to shore up an uncertain ally than by endorsing Zionist aims?

4. Britain adopted similar thinking when it came to the Russians, who were in the midst of their revolution. Several of the most prominent revolutionaries, including Leon Trotsky, were of Jewish descent. Why not see if they could be persuaded to keep Russia in the war by appealing to their latent Jewishness and giving them another reason to continue the fight?” …

Thus we have many factors:

The Jewish Zionist Movement, (initiated by Herzl a the end of the 19th century) Christian Zionism in the UK and the US – especially among government leaders, Britain’s imperial interests, and the appeal to Russian Jews.

The aim here – as Stephen has already opened up the role that Christian Zionism played in influencing the BD – is to discuss briefly certain aspects, the war situation, the imperialist aims of the British empire and the motives of the key players – meaning the British Government, the army, diplomatic initiatives – the promises and some of the key Arab and Jewish players – and to look at the immediate aftermath of the BD.

1. The British Empire – wider context

The Great War was to unexpectedly turned the imperial spotlight from the west to the east. It is well-known what was happening on the western Front – the agony of the deaths in the trenches of the Somme and sheer horror at the number of casualties – both British and French. (Many of us here will have had family involved). The disaster at Gallipoli. Look at the map to see what was at stake for the Empire- especially the route to India – which was still “the Jewel on the Crown” of the British Empire.

In understanding Empire at this time, we include

- colonies, (controlled by the British Government or companies- like the E. India Company controlled India); crown colonies;

- protected states – governed by a local ruler who had entered into a treaty with the British Government (United Arab Emirates);

- protectorates – foreign territories over which the British Government had political authority (but not sovereignty), but which lacked a local infrastructure that the British were prepared to deal with as equals; Egypt became a British protectorate in 1915.

- Dominions appeared in the late nineteenth century. These were former colonies (or federations of colonies) that had achieved independence and were nominally co-equals with the United Kingdom, rather than subordinate to it. An example would be the Irish Free State, a Dominion in 1922 from the territory of Ireland and which retained the Crown as head of state until the formation of the Irish Republic in 1949.

- Mandates were forms of territory created after the end of the First World War. In theory these territories were governed on behalf of the League of Nations for the benefit of their inhabitants. Most became converted to United Nations Trust Territories in 1946.

2. Alliances and Promises.

It is key to understand the way the alliances were going and what was at stake for key players.

As the Ottoman Empire had thrown its hand in with the Germans during WWI, it was inevitable – given the context of Empire – that the British would want to defend their strategic connection with India through the Suez Canal. The protection of the Persian Gulf was also important. And, in 1915 they would even try to force a way through to the Russians through the Dardanelles. So Palestine was suddenly thrust into becoming an active theatre of war.

At this period of time the most important indigenous group in Palestine that the British had to work with was the Arabs. The population of Palestine was about 700,000 – mostly poor peasants (fellahin). The number of Jews in Palestine were less than 60,000 at the outbreak of the war. (This number would grow with the successive waves of immigration – known as aliyah). 40,000 of these Jews could be described as indigenous, with roots on the land stretching back at least 2,000 years. The other 12,000 were Zionist pioneers who lived in scattered, but fortified Jewish settlements. So the Arabs, who formed 90 per cent of the population, understandably resented the Balfour Declaration’s reference to them as ‘the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’, a reference that Avi Shlaim calls ‘arrogant, dismissive and even racist’. This offending reference also implied there was one law for the Jews, and one law for everybody else.

2 initiatives are important:

The most important advance was when the British High Commissioner of Egypt, Lieutenant – Colonel Sir Arthur Henry McMahon, tried to co-opt the help of the Sharif Hussein of Mecca, in the fight against the Ottomans. (McMahon had been foreign secretary in India but had had no experience of the Middle East).

The Sharif of Mecca – Hussein Ibn Ali (1853-1931)- is one of our key players. He was appointed emir or Grand Sharif of Mecca by Sultan Amid II in 1908 and he led the revolt against the Ottomans in 1916. Despite his ambition to rule an Arab empire, the allies recognised him only as king of the Hejaz – a region in the west of present-day Saudi Arabia. [5]Its main city is Jeddah, but it is better known for the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina. His 3 sons figure also in the story- Ali, Abdullah (Emir/King of Transjordan) and Feisal – architect of the Arab revolt, colleague of T.E. Lawrence, (Lawrence of Arabia), King of Syria –briefly and then King of Iraq (1921).

In 1915 Britain promised Hussein, the Sharif of Mecca, that it would support an independent Arab kingdom under his rule in return for his mounting an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, Germany’s ally in the war. The promise was contained in a letter dated 24th October 1915, from Sir Henry McMahon, to the Sharif of Mecca in what later became known as the McMahon – Hussein correspondence. This correspondence seemed to promise the Arabs their own state stretching from Damascus to the Arabian peninsula in return for fighting the Ottomans. Before McMahon’s letter, Lord Kitchener (who was now minister of war in the British cabinet) had already promised Hussein that, if he would come out against Turkey, Britain would guarantee his retention of the title of Grand Sharif and defend him against external aggression. It hinted that if the Sharif were declared caliph he would have Britain’s support, and it included a general promise to help the Arabs to obtain their freedom.

However, not only was the correspondence deliberately imprecise but the status and ability of the Sharif of Mecca to speak for all of the Arabs was itself an issue. This is how the ambiguity appears:

‘In the Arabic version sent to King Hussein this is so translated as to make it appear that Gt Britain is free to act without detriment to France in the whole of the limits mentioned. This passage, of course, had been our sheet anchor: it enabled us to tell the French that we had reserved their rights, and the Arabs that there were regions in which they would have eventually to come to terms with the French. It is extremely awkward to have this piece of solid ground cut from under our feet. I think that HMG will probably jump at the opportunity of making some sort of ‘amende’ by sending Feisal to Mesopotamia’. JamesBarr, A line in the Sand, (London: Simon and Schuster 2011 p.118-119)

(This deliberate imprecision/ambiguity, not apparent in the Arab translation, became one of the bases for accusing Britain for breaking its promises).

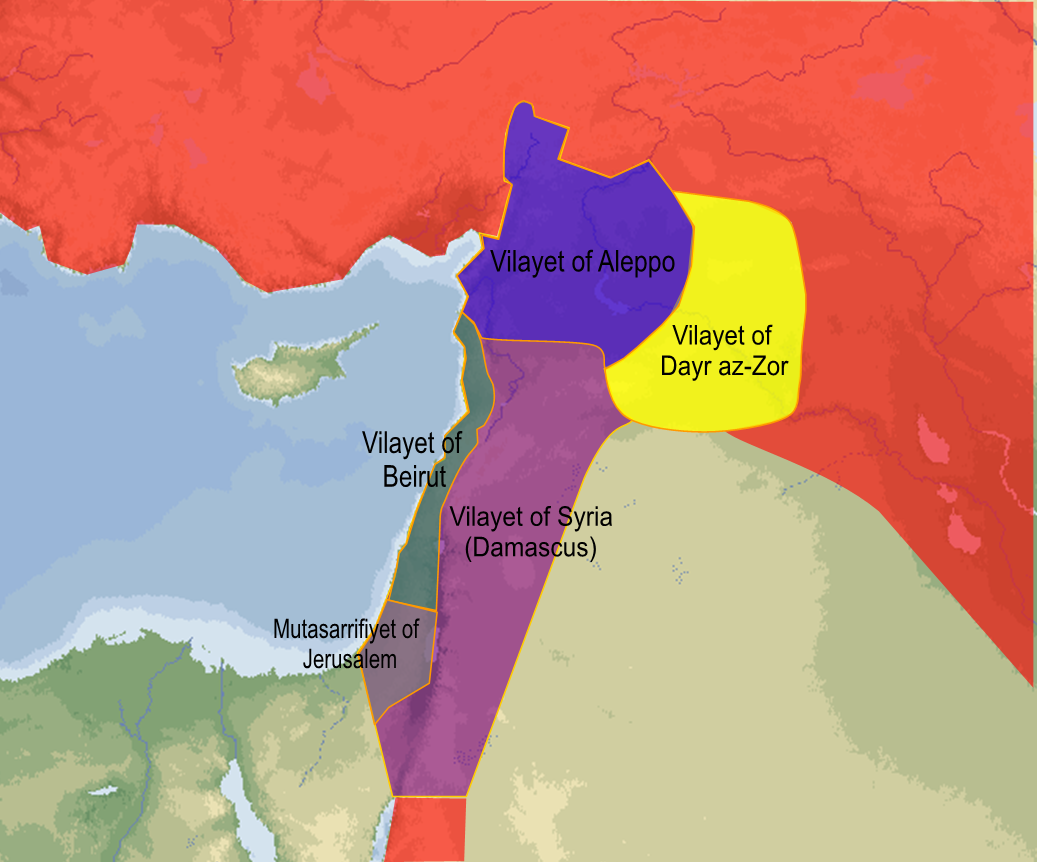

Administrative units in Near East under Ottoman Empire, to c. 1918

Administrative units in Near East under Ottoman Empire, to c. 1918

Despite these problems, the Sharif of Mecca did formally declare a revolt against Ottoman rule in 1916. Britain provided supplies and money for the Arab forces led by the Sharif’s sons, Abdullah and Faisal. British military advisers were also detailed from Cairo to assist the Arab army that the brothers were organizing. T.E. Lawrence would become the best known of these.

b. The second agreement that complicated the diplomatic waters was known as the Sykes – Picot agreement of 1916. Sir Mark Sykes was a baronet – 6th Baronet of Sledmere, charming, a Catholic –“but he wore this lightly,” passionate about the Middle East, anti-Semitic, but capable of changing his mind – he would became Weizmann’s staunchest ally and an ardent Zionist. Francois Picot was a diplomat, with expertise in the Middle East.

At the same time that Britain was negotiating with the Sharif Hussein over the future of the Asian provinces of the Ottoman Empire it was discussing the same subject with France and Russia and keeping the two sets of negotiations separate. It is difficult to argue that this was not being deceitful towards the Arabs, although the British could claim that they were involved in a deadly war with Germany and Turkey, and had to take account of their Allies’ wishes. In the event, Britain’s Arab policy evolved in a way that the British considered pragmatic, but which the Arabs came to regard as unprincipled.

This secret Anglo-French-Russian accord was reached in May 1916. This is how Jonathan Schneer describes it:[6]

It did not take long. Sykes was a human dynamo, bubbling with enthusiasm, teeming with ideas…Picot was urbane and reserved…The two men developed a working relationship that they preserved for the duration of the war. ..together Sykes and Picot redrew the Middle Eastern map. We may picture them in the grand conference room in the Foreign Office, crayons in hand. They coloured blue the portions on the map they agreed to allocate to France, and they coloured red the portions they would allocate to Britain….Since both parties coveted Palestine, with its sites holy to Christians, Jews and Muslims alike, they compromised and coloured the region brown, agreeing that this portion of the Middle East should be administered by an international condominium.

In fact the outcome was that the areas would become British and French spheres of influence – (The details were later modified) – but the agreement meant a clear decision to divide the whole of what is today’s Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan and southern Turkey into spheres of British or French control or influence, leaving only Jerusalem and part of Palestine (on Russian insistence) to some form of international administration. Only the area comprising the present-day Saudi Arabia and the Yemen Arab Republic were to be left independent. For understandable reasons, Britain and France chose to keep this agreement secret. But as the war developed, Sharif Hussein became increasingly suspicious of the Allies’ intentions, and in early 1917, Sir Mark Sykes was sent to Jedda by the British Foreign Office to allay his fears. But although they discussed the question of French arms in Lebanon and the Syrian coastal regions, with Hussein maintaining the principle that these regions were as much Arab in character as the interior, Sykes did not inform him of the broader aspects of the Sykes-Picot agreement. Many of these clauses contradicted promises made to the Sharif. It would be the Turks who informed Hussein.

3. Who were the key players in the British Government involved in the BD?

First, Asquith – Herbert Asquith, Herbert Henry (First Earl of Oxford and Asquith) 1852 -1928 was a liberal politician: important as prime minster from 1908-1916 he led Britain into the First World War with France as ally. However following a Cabinet split on 25 May 1915, caused by the Shell Crisis (or sometimes dubbed ‘The Great Shell Shortage’) and the failed offensive at the 1915 Battle of Gallipoli, Asquith became head of a new coalition government, with David Lloyd George, bringing senior figures from the Opposition into the Cabinet.

At first the Coalition was seen as a political masterstroke, as the Conservative leader Bonar Law was given a relatively minor job (Secretary for the Colonies), whilst former Conservative leader Arthur Balfour was given the Admiralty, replacing Churchill. Lord Kitchener, popular with the public, was stripped of his powers over munitions (given to a new ministry under Lloyd George) and strategy (given to the General Robertson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who was given the right to report directly to the Cabinet: Critics increasingly complained about Asquith’s lack of vigour over the conduct of the war. Lloyd George succeeded him as Prime Minister in December 1916.

The War Cabinet (WW1)

The creation of the War Cabinet undertook the supreme direction of the war effort. It was composed of David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour now Foreign Secretary replacing Edward Grey, Andrew Bonar Law, Lord Nathaniel Curzon, Alfred Milner, Arthur Henderson and Sir Maurice Hankey (its Secretary). Mark Sykes and Leopold Amery were also secretaries.

Both Lord Curzon and Edwin Montaguwere against the declaration. Curzon, (First Marquess Curzon of Kedleston) 1859-1925, a conservative politician, formerly viceroy of India from 1898- 1905 joined Asquith’s government in 1915. Invited by Lloyd George to join his government in 1916 as well as the (select) War cabinet, he served as lord president of the council. After the war Curzon replaced Balfour as Foreign Secretary and served until the Labour victory in the general election of 1923.

His relevance for the Balfour Project is that Curzon was strongly opposed to Zionist aims in Palestine and argued that Jewish immigrants would not be able to establish a homeland there without expelling the indigenous Arabs. Although he managed to include a commitment to the ‘non-Jewish communities’ in the Balfour Declaration, he remained convinced that the policy was mistaken, ‘the worst’ of Britain’s Middle East commitments and ‘a striking contradiction of our publicly declared principles.’ [7]

Edwin Montagu (1879- 1924) was a Jewish anti-Zionist and liberal politician with close ties to Asquith. He earned the latter’s enmity by joining the Lloyd George coalition government and led the opposition in the Cabinet to the Balfour Declaration: his view was that he had spent his life as a British citizen and did not want to return to a “Jewish Ghetto”. But just before the Cabinet came to a final decision, he had to leave the country to take up a post as Secretary of State for India.

The Christian Zionist dimension among Cabinet members was strong and growing – especially Balfour himself and Lloyd George –but also Henderson, Barnes. Edward Carson (representing Ulster) was silent. Bonar Law’s views are unknown. Balfour was one of the oldest and most influential member of the Cabinet – and very influenced by Weizmann, whom he had met in 1906.The famous conversation between the two is worth retelling.

‘Mr Balfour , suppose I was to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?’

‘But Dr Weizmann, we have London’, said Balfour.

‘True, but we had Jerusalem’, relied Weizmann, who knew that most Anglo-Jewish grandees scorned Zionism, “when London was a marsh”.

“Are there many Jews who think like you?”

“I speak the mind of millions of Jews.”[8]

Already in 1906 Balfour had written to a niece saying that he could see no political difficulty about obtaining Palestine, only economic ones. [9]

Later, after the start of the Great War in 1914, Weizmann was summoned by Winston Churchill, then first Lord of the Admiralty, who was keenly interested in his discovery of manufacturing acetone which could be used in the making or cordite explosives for the war effort. [10]It was at that point that Weizmann discovered an interest in Zionism in the Cabinet. It was Lloyd George, then minister of munitions, (who had earlier represented Zionists as a lawyer) who introduced him to Balfour. At this point Weizmann and Balfour began to meet regularly, “strolling around Whitehall at night and discussing how a Jewish homeland would serve, by the quirks of fate, the interests of historical justice and British power”. [11]

Tom Segev relates how, one night, Balfour and Weizmann walked backwards and forwards for two hours, after the latter had dined with Balfour:

The Zionist movement spoke, Weizmann said, with the vocabulary of modern statesmanship, but was fuelled by a deep religious consciousness. Balfour himself, a modern statesman, also considered Zionism as an inherent part of his Christian faith. It was a beautiful night; the moon was out. Soon after, Balfour declared in a Cabinet meeting, “I am a Zionist.”[12]

Added to the sincere Biblical motivation- the return of the Jews to their “origins” – was linked the sympathy for the plight of Russian Jews. Tsarist repression had intensified during the war. Both Balfour and Churchill had an almost mystical conviction of the giftedness of the Jewish race. In addition, American policy might be favourably influenced if returning the Jews to Palestine became part of British policy. Furthermore, the Germans were also considering a pro-Zionist declaration!

Many of these factors would come together in the signing of the Balfour declaration, when, at this juncture, the Asquith government fell (December 1916), and Lloyd George became prime minister.

I want to factor in 2 subjects- Allenby’s campaigns and Weizmann’s efforts:

(Factor in now that Sir Edmund Allenby, (1861-1936)promoted to general for his distinguished record on the Western Front(WW1) was sent to Egypt to be made commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) on 27 June 1917. His forces captured Gaza in October, Jerusalem in December and Damascus in October 1918. So the negotiations concerning the Balfour Declaration had as background Allenby’s conquests in Palestine.

Allenby needs mentioning for another reason: Why did Allenby remain silent on the declaration, censoring all mention of it as he launched his great offensive? The best answer to this question can be derived from Allenby’s biographer, General Wavell, who noted that:

‘… with the entry into Palestine and capture of Jerusalem political as well as military problems began to occupy Allenby. Palestine presented some very thorny and difficult questions. The awkwardness of reconciling our pledges to the Arabs, our undertakings to our Allies (the Sykes-Picot Agreement), and the Balfour Declaration to the Zionists was already becoming evident to those who knew of them … He refused to allow the Balfour Declaration to be published in Palestine.’

So it wasn’t – for another 3 years.

Chaim Weizmann was born in Russia in 1874, in Motol, now Belarus, but then in the “Pale of Settlement”, that area of Russia to which the Jews had been confined since the time of Catherine the Great. From an early age he became interested in chemistry and managed to study in Berlin and then Freiburg in Switzerland. He met his future wife Vera Chatzman in Switzerland. He was the whole time seeking for ways to realise the Zionist dream. Theodor Herzl’s death was a huge blow to him and he left for England in 1904 where he became a biochemistry lecturer at the University of Manchester and soon became a leader among British Zionists. In fact he told his wife that the two passions of his life were Zionism and chemistry. Passions that endured to the end of his life.

After the famous conversation with Balfour in 1906 (cited) it was clear that it was the spiritual side of Zionism that appealed to Balfour. But it would be a further eight years before the two men met again. It was a frustrating time for Weizmann who travelled the country trying to promote unity in the Zionist cause. There was much opposition from the conservative Rabbinate who thought that to bring the Jews back to the Promised Land was a blasphemous anticipation of the biblical millennium. In 1907 he first visited Palestine which he considered “a dolorous country on the whole, and Jerusalem in particular he thought was a “miserable ghetto, derelict and without dignity.”

In 1914 Weizmann met Baron Edmond de Rothschild. The latter was not a Zionist but a great philanthropist and saw the value of Weizmann’s lifelong dream of a Hebrew University in Palestine.

In the next few years Weizmann would meet with influential people – like Herbert Samuel and C.P.Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian – and become aware of the opposition of others, like Edwin Montagu.

(Events become increasingly complex as two contradictory processes got underway. (Sykes-Picot and the McMahon Letter- not be published until 1939).

Although the Zionists were ignorant of both of these agreements until much later, their aspirations for Palestine were well-known to members of the British government – to Herbert Samuel, Edward Grey and Arthur Balfour, for example. Events moved forward when Sykes’ enthusiasm for Zionism grew – as did the involvement of American Jews. A legend has grown up because of what Lloyd George wrote in his autobiography, that the Balfour declaration was a reward for Weizmann’s work in biochemistry for the Admiralty. His most important discovery was the production of acetone on a large scale by bacterial fermentation: even though Weizmann was underpaid and his work never achieved the acclaim it deserved – or the chair in Manchester he hoped for- it at least brought him into contact with Lloyd George. Industrial scale production of acetone would begin in six British distilleries requisitioned for the purpose in early 1916. The effort produced 30,000 tonnes of acetone during the war, although a national collection of horse-chestnuts was required when supplies of maize were inadequate for the quantity of starch needed for fermentation![13]

But the suggestion that Palestine was his reward was a figment of Lloyd George’s imagination. As Weizmann commented:

I almost wish it had been as simple as that, and that I had never known the heartbreak, the drudgery which preceded the Declaration. But history does not deal in Aladdin’s lamps. [14]

By the time Lloyd George became Prime Minister he no longer had any doubts about Palestine. The end of 1916 and beginning of 1917 saw a sea change in attitudes, with a convergence of interest between British interest and Zionist opportunity: the change of government, the Russian Revolution, the United States entered the war, and Britain invaded Palestine – these were all key factors. Balfour had now moved from the Admiralty to the Foreign Office.

In 1917 Weizmann became president of the British Zionist Federation and the de-facto leader of World Zionism. Nahum Sokolow was his chief collaborator. At the suggestion of Mark Sykes with whom he worked closely, Sokolow travelled to France and Italy during the spring of1917 and gained support from those countries for Zionist objectives. He was intimately involved from the Zionist side with the discussions that produced the Balfour declaration.

A founder of so-called Synthetic Zionism, Weizmann supported grass-roots colonization efforts as well as high-level diplomatic activity. He was generally associated with the centrist General Zionists and later sided with neither Labour Zionism on the left nor Revisionist Zionism on the right. In 1917, he expressed his view of Zionism in the following words:

We have [the Jewish people] never based the Zionist movement on Jewish suffering in Russia or in any other land. These sufferings have never been the mainspring of Zionism. The foundation of Zionism was, and continues to be to this day, the yearning of the Jewish people for its homeland, for a national center and a national life.

After a meeting on the 19th June, when Weizmann told Balfour firmly that the time had come for the Zionists to be given some definite encouragement, Balfour asked him to put together a proposal which he, Balfour, could put before the cabinet. Thus began Weizmann’s final effort to obtain the milestone Balfour Declaration. There were a still many obstacles – in particular the lack of unity among Jewish groups, especially the opposition of significant figures like Claude Montefiore and Lucien Wolf, and the efforts of Vladimir Jabotinsky – eventually unsuccessful – a Russian Jew and a friend of Weizmann to set up a Jewish battalion to fight in Palestine.

The drafting team- which included Mark Sykes and two officials – Leopold Amery and Harold Nicolson – sent a draft on the 18th July, but it was not considered until September 3rd. There was much opposition – especially a passionate and poignant plea from Edwin Montagu. The attitude of the American President, Wilson, was also crucial and a “favourable” letter from him was read out at the Cabinet meeting of October 4th, plus a sympathetic letter which Sokolow had obtained from the French government in June. (This French agreement is often omitted from official memory).

Balfour gave British Jewry a last chance to express their opinions and Weizmann engaged in furious activity, attempting to get hundreds of synagogues and Jewish groups to support the initiative. The Chief Rabbi contributed his spiritual authority. Despite the intervention of Lord Curzon, the continued opposition of Montagu , the Declaration was passed on November 2nd – 95 years ago exactly– and Balfour sent the historic letter to Lord Rothschild.

The Letter stated in part that the British government “views with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people … “. At no point had the situation of the Arab people been considered: nor had they been acknowledged as rightful owners of the land.

What happened has become the stuff of legend: Sykes rushed out to an antechamber, where Weizmann was waiting:

“Dr Weizmann, it’s a boy!” “Well,” wrote Weizmann afterward, “I did not like the boy at first. He was not the one I had expected. But I knew this was a great event. I telephoned my wife, and went to see Aha Ha’am.” [15]

This was the most significant achievement of Weizmann’s life.Though not his last achievement, history would judge the Balfour Declaration one the greatest obstacles to securing peace in Palestine – especially after events in 1948. For the rest of Weizmann’s long life, he played a leading role in World Zionism, in the developing state of Israel as its first President, and in the foundation of the Hebrew University of his dreams, to this day a highly respected Weizmann Institute of Science at Rekovot.

After the war, on 3 January 1919, Weizmann and Prince Faisal signed the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement attempting to establish favourable relations between Arabs and Jews in the Middle East. At the end of the month, the Paris Peace Conference decided that the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire should be wholly separated and the newly conceived mandate-system applied to them.

5. Another key character- especially after the BD -is Herbert Samuel:(- 1870-1963)

A Liberal politician who rose to become President of the Board of Trade and then Home Secretary in Asquith’s cabinet, he came from the “cousinhood” of wealthy, assimilated Jewish British. He had developed the Zionist position further in a talk with the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Sir Edward Grey, on 9 November 1914:

. ‘I spoke to Sir Edward Grey to-day about the future of Palestine. In the course of our talk I said that now that Turkey had thrown herself into the European War and that it was probable that their empire would be broken up, the question of the future of Palestine was likely to arise … Perhaps there might be an opportunity for the fulfilment of the ancient aspiration of the Jewish people and the restoration there of a Jewish State.’

Samuel went on to say: ‘If a Jewish State were established in Palestine, it might become the centre of a new culture. The Jewish brain is rather a remarkable thing, and, under national auspices, the State might become a fountain of enlightenment and a source of a great literature and art and development of science.’ Samuel continued that his note (for November 9th) proceeded as follows: ‘Grey said that the idea had always had a strong sentimental attraction for him. The historical appeal was very strong. He was quite favourable to the proposal and would be prepared to work for it if the opportunity arose.’[16] It seems that Grey, however, did not envision the creation of a political entity in Palestine, and considered such views from the angle of establishing a Jewish cultural centre. Grey’s views were said to have been conveyed by Weizmann, the chief Zionist negotiator, to the Zionist International.[17]

Samuel also reveals that before that date he had had no connection with the Zionist movement, but now, ‘suddenly, the conditions were entirely altered’. He went on to say:

‘As the first member of the Jewish community ever to sit in a British Cabinet— (Disraeli had left the community in boyhood and never rejoined)—I felt that, in the conditions that had arisen, there lay upon me a special obligation.’

In a speech later Herbert Samuel informed his audience that he had then made a study of Zionism and its achievements and knew all that there was to know about Palestine. Later he helped to bring Weizmann into contact with other important British officials. After the war he was Britain’s first High commissioner in Palestine.

6 Conclusion- a Broken Trust

1.According to Shlaim, by a stroke of the imperial pen, the Promised land [thus] became twice promised. Even by the standards of Perfidious Albion, this was an extraordinary tale of double-dealing and betrayal, a tale that continued to haunt Britain throughout the 30 years of its rule in Palestine.[18] The extraordinary fact is that no one was found who really remembered the motivation for the BD. Balfour when approached later had lost his memory. He said that Mark Sykes would have it at his finger tips- but he had already died in 1922 of Asian flu.

2. The ambiguity that was inherent in the wording of the declaration caused considerable confusion in the years immediately following its issuance. When a new Conservative government came to power at the end of 1922, at a time when British public support for the government’s pro-Zionist policy was rapidly declining, the British government came under pressure from members of parliament as well as the press to define the meaning of the Balfour Declaration. It was against this background that the British Colonial Office, responsible for Palestine since 1921, set out to give an official explanation of the Balfour Declaration. What resulted was the first ‘official interpretation’ by any British government of the declaration.

3. The debate was started when an Arab Palestinian delegation[19] to London published in the British press parts of the Hussein-McMahon correspondence of 1915, in which the British promised Sherif Hussein independence. The Arab delegation drew the attention of the British public that the Balfour Declaration was in direct violation to these previous pledges, since Palestine was included in the area in which Arab independence was promised by McMahon to Hussein. In this atmosphere, the Colonial Office was compelled to look into the origins of the Balfour Declaration and its pro-Zionist policy, in order to come to an early decision on whether it should uphold or reverse this policy.

4. But, a journalist, M.N. Jeffries stated: Whatever is to be found in the Balfour Declaration was put into it deliberately. There are no accidents in that text. If there is any vagueness in it this is an intentional vagueness.’[20]

5. Also crucial: the lack of archival evidence as to what was said: – Although there is an overwhelming amount of literature on the events leading up to the Balfour Declaration (from April to November 1917), British archival sources reveal an alarming lack of documentary evidence on its earlier history. In this context, an important minute by the undersecretary for the Colonies in 1922, William Ormsby-Gore, describing from memory the events leading to the declaration, is crucial:

‘I think it is very important that the story of the negotiations which led up to the Balfour Declaration of Nov. 2nd 1917 (before General Allenby’s first great advance) should be set out for the Secretary of State and possibly the Cabinet. The F.O. and Sir Maurice Hankey both have material. The matter was first broached by the late Sir Mark Sykes early in 1916, and he interviewed Dr Caster and Sir Herbert Samuel on his own initiative as a student of Jewish politics in the Near East. Dr Weizmann was then unknown. Sykes was furthered by General MacDunagh [sic], DMI [Director of Military Intelligence] as all the most useful and helpful intelligence from Palestine (then still occupied by the Turks) was got through and given with zeal by Zionist Jews who were from the first pro-British. Sir Ronald Graham took the matter up keenly from the Russian and East European point of view and early in 1917 important representations came from America. The form of the Declaration and the policy was debated more than once by the War Cabinet, and confidential correspondence (printed by Sir Maurice Hankey as a Cabinet paper) was entered into with leading Jews of different schools of thought. After the declaration, the utmost use was made of it by Lord Northcliffe’s propaganda department, and the value of the declaration received remarkable tribute from General Ludendorf. On the strength of it we recruited special battalions of foreign Jews in New York for the British army with the leave of the American government.

The S of S [Secretary of State] should have a statement showing similar declarations by other powers up to and including the recent one of the American Senate, and also a summary of what has been done by the Jews already in Palestine, i.e. 4 millions of money, schools etc. Some of the Zionist organizations [sic] election leaflets were really rather effective. The Balfour Declaration in its final form was actually drafted by Col. Amery and myself. I wrote an article on the question in the XIXth Century about 2 years ago which has some interesting data’.[21] WOG 24/12/1922

6. Balfour 1919:

In a secret memorandum to the British cabinet, Respecting Syria. Palestine and Mesopotamia, Balfour wrote in 1919:

‘… Take Syria first. Do we mean, in the case of Syria, to consult principally the wishes of the inhabitants? We mean nothing of the kind… So whatever the inhabitants may wish, it is France they will certainly have. They may freely choose; but it is Hobson’s choice after all … The contradiction between the letter of the Covenant and the policy of the Allies is even more flagrant in the case of the ‘independent nation’ of Palestine… For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form for consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country.’[22]

On 11 August 1919, Balfour had stated that the four Great Powers were committed to Zionism, and that ‘Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land … ’[23]

A Broken Trust?

[1] Balfour 1848-1930. PM 1902-1905; Foreign Sec. 1916-1919.

[2] Leonard Stein (The Balfour Declaration, London, 1961)

[3] David Fromkin, A Peace to end all Peace, p.282.

[4] Shlaim, p. 10.

[5] Defined primarily by its western border on the Red Sea, it extends from Haql on the Gulf of Aqaba to Jizan. As the site of Islam’s holy places the Hejaz has significance in the Arab and Islamic historical and political landscape. The region is so called as it separates the land of Najd in the east from the land of Tihamah in the west).

[6] Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration, (London: Bloomsbury 2010), p.79.

[7] Curzon to Bonar Law, 14 Dec 1922, Parl. Arch., Bonar Law MS 111/22/46).

[8] Simon Sebag Montefiori, Jerusalem: the Biography, p. 410.

[9] Cited by Stephen Sizer, Christian Zionism- Roadmap to Armageddon, (Leicester: Inter-varsity Press 2004, p.63.

[10] The story was later invented by Lloyd George in his memoirs that the Balfour Declaration was given to Weizmann as a reward for his invention of maize-acetone. His invention was important for the war effort, but the link was invented. (Fromkin, op cit.,p.285).

[11] Montefiori 412.

[12] Segev, p.41. From The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann.

[13] Weizmann is considered to be the father of industrial fermentation. He used the bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum (the Weizmann organism) to produce acetone. Acetone was used in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants critical to the Allied war effort (see Royal Navy Cordite Factory, Holton Heath). Weizmann transferred the rights to the manufacture of acetone to the Commercial Solvents Corporation in exchange for royalties.

[14] Weizmann, Trial and Error, (London: Hamish Hamilton 1949).

[15] Weizmann, Trial and Error, p.262.

[16] Ibid., pp.12-13.

[17] John and Hadawi, op. cit., pp. 60-61.

[18] Shlaim, p. 4.

[19] The Palestine Arab delegation spent one year in London, from mid-1921 to mid-1922, in the hope of persuading the British government to annul the Balfour Declaration. Although the delegation succeeded in cultivating the support of many British politicians as well as the British press to its cause, the Middle East Department, where the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann was a regular visitor, was successful in thwarting such interaction. During the mandate years, (1920-48) the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration was received with loud Arab protests and demonstrations. The 2nd of November of each year was a day of ‘mourning’ in which black flags were flown from the windows of Arab shops and houses. Moreover, all Arab congresses since 1918 firmly rejected the Balfour Declaration.

[20] See Jeffries, J M N,Analysis of the Balfour Declaration, in Khalidi, Walid. From Haven to Conquest, (ed.) Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut 1971, pp. 173-4.

[21] CO 733/28. The last paragraph of Ormsby-Gore’s handwritten minute was omitted from the printed version of the above mentioned Cabinet Paper. Ormsby-Gore’s minute will be analysed in detail on pp. 72-121 below. (See Appendix A for original handwritten minute C0733/35). When Ormsby-Gore wrote this minute, he had just been appointed Under Secretary of State for the Colonies. It may be of interest to note that a writer in the Hebrew Doar Hayom wrote on 3 Nov 1922 expressing the view that he was optimistic about the future now that Ormsby-Gore was appointed Under Secretary of State for the Colonies, and that this was a very important gain for the Zionist cause.

[22] Khalidi, W, op. cit., see Introduction, also pp. 201-213.

[23] Memorandum by Balfour, August 11, 1919. See Khalidi W, ibid., p. 226.

![200px-arthur_balfour_photo_portrait_facing_left[1]](https://balfourproject.org/bp/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/200px-arthur_balfour_photo_portrait_facing_left1.jpg)