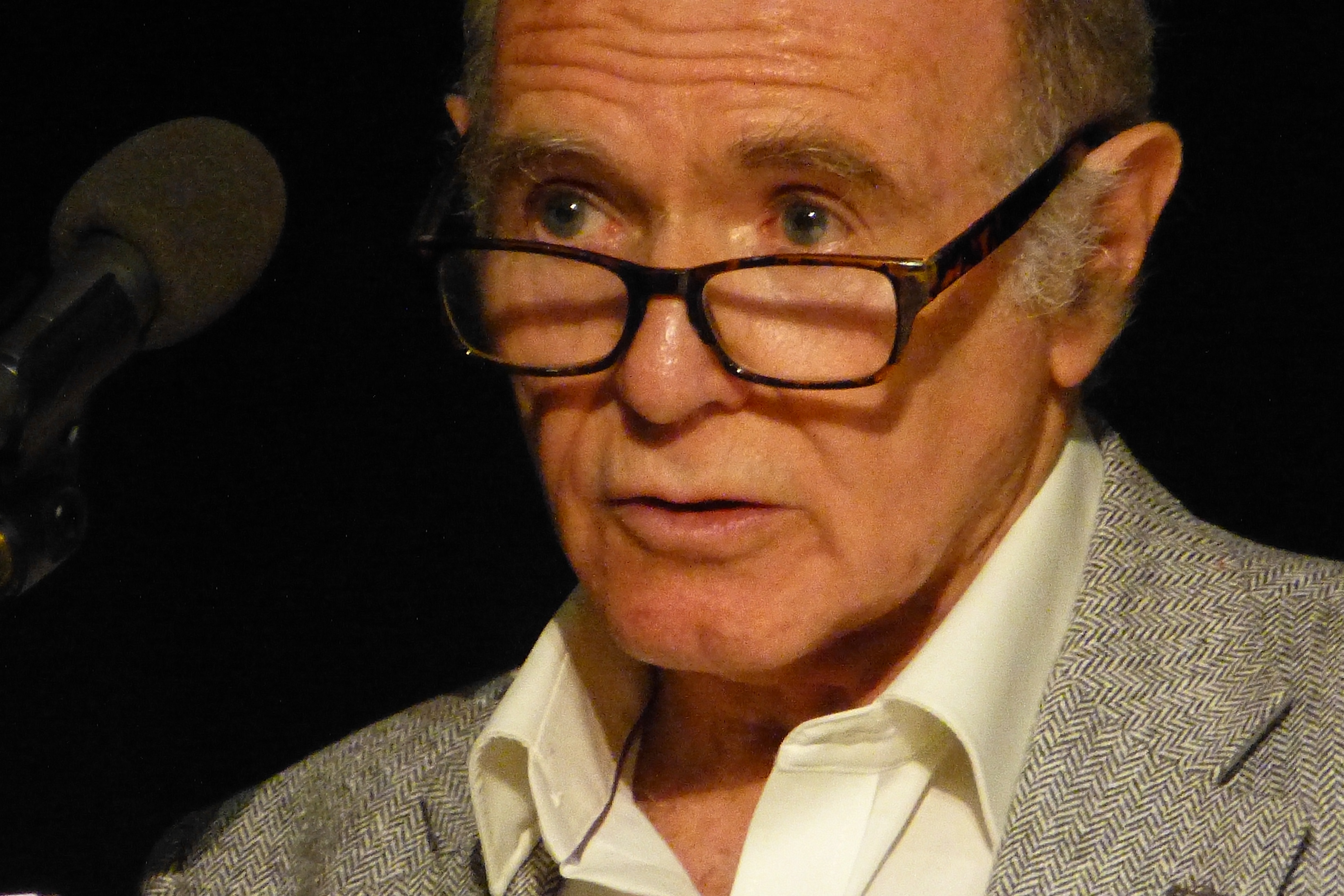

Tony Klug, speaking at the Balfour Project conference in October 2013 spoke stirringly to the question “Are we trapped by our own narratives?” He began by demonstrating that everyone becomes a player in this seemingly intractable conflict, where what passes for objective analysis masks partisan agenda. He urged empathetic understanding of key protagonists on both sides of the conflict. This demands moving out of our comfort zones and exclusive adherence to one narrative.

speaking at the Balfour Project conference in October 2013 spoke stirringly to the question “Are we trapped by our own narratives?” He began by demonstrating that everyone becomes a player in this seemingly intractable conflict, where what passes for objective analysis masks partisan agenda. He urged empathetic understanding of key protagonists on both sides of the conflict. This demands moving out of our comfort zones and exclusive adherence to one narrative.

Since the core of the issue is that a homeland was given to the Jewish people because of centuries of discrimination, the Palestinians paying the price with being dispossessed of their own land, (the core reasons being anti-Semitism at home and imperialism abroad), he then asked – where does this all lead?

Despite the Algiers Agreement in 1988 as to a 2-State Solution, the Israeli government still seems intent on encroachment on Palestinian land; unless something happens, Tony Klug would expect a 3rd Intifada. Here is the point at which the EU and UK should step in assertively demanding change. Arab States too might show what normal relations with Israel might look like. We should believe that what we imagine could become a reality!

A video of his talk is here and the text below:

I want to begin this evening with a conundrum, one that I first posed earlier this year at a conference in Amman, Jordan. What, I asked, do the following pivotal events have in common?

The 1967 Arab-Israel war.

The 1973 Arab-Israel war.

The Sadat Initiative.

The first Palestinian Intifada.

The Oslo Accord.

The second Palestinian Intifada.

The uprooting of all Israeli settlements in Gaza.

The 2006 election victory of Hamas.

The Arab uprisings.

The mass social protests in Israel.

The 2013 election result in Israel.

The tearing apart of Syria.

The answer is that none of them was anticipated.

In retrospect, clever experts were of course able to explain, with great clarity, why these events came about. Even, in some cases, why they were all but inevitable. But, for the most part, only after they occurred. I can say this with a degree of confidence because, from time to time, I’ve been guilty of this myself.

The question I did not go on to pose in Amman – I was developing a different theme there – is why is this? What is it about the Arab-Israel-Palestine imbroglio that makes it so difficult, time and again, to foresee the vital turning points in advance of them happening? It is true that decisive changes in other regions of the world sometimes also defy prediction, but the record in relation to this conflict is close to unassailable. Indeed, it is hard to conceive of an exception.

It is an intriguing question, for which I don’t have a definitive answer. But something I have observed over the years of my involvement is that one of the distinguishing features of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is that almost everyone who engages with it is, or soon becomes, a stakeholder of sorts in the problem. Inevitably, this moulds the way we view events. Even the most seasoned of commentators and analysts are prone to ‘take a side’.

Sometimes this is quite overt, sometimes it is more subtle — even to the point where we may not actually be aware of it ourselves. Sometimes, the ‘side’ we take may be just an acute frustration with both parties — “a fire on both their houses” or “they deserve each other” are not uncommon invectives. But even this is a position and is liable to influence the holder’s take on events.

Directly or indirectly, consciously or subconsciously, we become players. What we present as analysis is often veiled advocacy. Our impartial ‘facts’ are frequently selected to comply with our witting or unwitting predilections. Our supposedly neutral future projections may be little more than a function of our own desires or delusions or despondencies. Developments outside the framework of our psychological boundaries or emotional affinities are thus apt to catch us unawares.

What is true for outsider pundits who often believe themselves to be above the fray is, by and large, true in buckets for the main parties to this conflict and their global cheerleaders. The extrapolations of partisan voices to this – or any – dispute are rarely reliable guides to the way events will actually unfold in the real world.

Quite recently, I attended a seminar organized by a pro-Israel group. A few days earlier, I had attended a conference hosted by a pro-Palestinian group. The participants at both meetings — with some notable exceptions — came across as reasonable, decent, liberal-minded people with an abiding commitment to human rights. Certainly, they regarded themselves as such.

But, on the whole, you would not believe they were talking about the same conflict. One meeting’s certainties were the opposite of the other meeting’s certainties. One side’s heroes were – I suppose naturally — the other side’s villains. Where there was apparent common ground, such as on the allegedly notorious bias of the press, there was almost total divergence on the direction of the bias. One problem is that when essentially like-minded people gather together, pre-existing Illusions tend to get reinforced rather than face a challenge.

It has been my custom for decades to accept invitations from both camps. I note, with regret, that this is not a common practice. I say ‘with regret’ because if we, as outsiders, wish to influence the future course of events in a way that contributes to the resolution of the conflict –rather than to its exacerbation — we need to acquire an empathetic understanding of the factors that shape the thinking, reasoning and behaviour of the principal protagonists and the way they view events. It is not enough to have this intuition just for the side to which we are instinctively drawn. To act out of knee-jerk solidarity does not necessarily do a service to anyone, even to the cause of the party we favour.

A possible insight into what causes people to take this or that side in the first place may be provided by an old adage, attributed to Abraham Lincoln, that goes something like this: “If you were born where they were born and you were taught what they were taught, you’d believe what they believe”.

While falling short of a complete general theory — and certainly there are exceptions — this simple dictum does, I think, go some way to explain not just what we believe but why we believe it. Why we take up certain positions and hold them so fervently. Why Jews, in the main, have historically supported Israel and seen the Palestinians as an irritant or worse. Why Arabs and Muslims, as a rule, have supported the Palestinian cause and seen Israel as an interloper or worse. And why both sides have been equally convinced they were in the right.

What would we believe -– each of us — if we hailed from the other side of the track or river or mountain? What ‘facts’ would we then be predisposed to accept as self-evident truths and which ones, by contrast, would we be inclined summarily to dismiss as propaganda lies? And what of the dedicated fanatics among us? Would their support of the opposing cause be any less partisan or extreme or self-righteous if they happened to be born on the other side of the mirror?

None of this is to suggest that facts are merely subjective. Nor that there are not genuine questions of historical interpretation, justice, legality or human rights. Of course there are. What is suggested, though, is that, to move forward, we need to acquire the ability to view matters beyond our comfort zones and to think outside of our boxes.

So many of us are trapped in and by our own narratives and we devote enormous resources to justifying and reinforcing our own perspectives and simultaneously to belittling or ridiculing the other’s. This is not the prerogative of any one side. All sides do it. Self-appointed experts churn out, and their followers dutifully cite, reams of supposedly scholarly research that ‘prove’, for example, the non-authenticity of the people-hood or nationhood of the other — thus disqualifying them from competing for territory in the first place — and the non-validity of many of their cherished claims. “There is no such thing as the Jewish people!”, asserts one supposed expert. “A Palestinian nation is pure invention!”, claims another. We can think of many other examples.

These commonplace writings, driven by the essentially negative motive to demonstrate as non-existent a phenomenon that is regarded as undesirable are, in general, completely without value. They perpetuate stereotypes and add nothing to the sum total of human knowledge or wisdom. Their solutions — however they are dressed up -– invariably involve the capitulation or subordination of the adversary. They offer no real answers. They just condemn us all to endless conflict.

Indeed, there is a serious risk of this. But such a future is not pre-ordained. It is not as if there is a deep-seated ideological or religious dispute between these two small peoples or an endemic historical enmity. Israelis and Palestinians have clashed — bitterly -– in recent times fundamentally because they simultaneously aspired to the same piece of territory on which to exercise their self-determination. If the geographical targets had been different from each other, it would not have been so hard to imagine the relationship between these two long-suffering peoples as one of alliance and mutual support. And, as far-fetched as this may seem at present, it could still be. In many respects, they have much in common.

So what of these different core perspectives? Let’s take a quick look at the essence of each in turn.

The underlying case for a Jewish homeland was strikingly, if inadvertently, put by the poet Lord Byron, as far back as 1815, when some of the worst tragedies to face the Jewish people, including the tsarist pogroms and the Nazi Holocaust, still lay a distance ahead. This was several decades before Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, was a twinkle in anyone’s eye, and a full century before the Balfour Declaration of 1917. In his ‘Hebrew Melodies’, Byron, who was not of Jewish heritage himself, wrote: “The wild dove hath her nest, the fox his cave, mankind their country, Israel but the grave!” By “Israel,” of course, he meant the Jewish people.

Once the Zionist movement eventually came into being, however, all sorts of conspiracy theories and malevolent intent were soon fastened onto it by its detractors, some of it giving off a familiar antisemitic whiff, not so different from that which played the decisive role in winning so many Jews and others to the Zionist cause in the first place.

Conceptually, Zionism was a distressed people’s proud, if defiant, response to centuries of contempt, humiliation, discrimination and periodic bouts of murderous oppression. The Israeli state was the would-be phoenix to rise from the Jewish embers still smouldering in the blood-soaked earth of another continent. The underlying motive, in the eyes of its proponents, was the positive one of achieving safety and justice for a tormented people, not the negative one of doing damage to another people. Yet, in effect, this is exactly what it did do and, as discomfiting as it may be, Israelis and their supporters around the world will, at some point, have to come fully and openly to terms with this.

In the attempt to rectify the enduring Jewish calamity, a second people was obligated to pay a heavy price. The ill-fated Palestinians, in common with their Arab brethren in neighbouring countries and other colonized peoples, had long yearned for their independence free from foreign rule, only to find that, in their case, another people, mostly from foreign parts, was simultaneously laying claim to the same land. Naturally, the Palestinians resisted. Any people would have resisted. In their place, Israelis most certainly would have resisted.

The Palestinians, in like fashion, did not set out to damage anyone but aspired to what they felt was rightfully theirs. Dispossessed, degraded and deserted, they were among the principal losers in the geopolitical lottery that followed the horrors of the Second World War. They were, in a sense, the knock-on victims of Nazi atrocities. Their original felony was, in essence, to be in the way of another distressed people’s frantic survival strategy. Virtually everything that has happened since then is in some way a consequence of this.

This tragic historical clash — the product of centuries of virulent European antisemitism at home and rampant imperialism abroad, crowned by double or, in this case, treble dealings — is the root of the conflict. Almost everything else has been grafted on retrospectively. Self-serving explanations of the type that portray either people as innately wicked or falsify their histories or disparage their sufferings do not in any way aid understanding of the problem. They merely confound the issues, deepen the hatred and poison the air. The core case for each side stands proud in its own right. Neither one is nullified because the other side also has — in its own terms — a strong and valid case.

In the real world of today where, in practical terms, does all this leave us? Some forty years ago, in a Fabian pamphlet, I called for the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel. I made this proposal because it seemed blindingly obvious from my own research, travels and personal engagements that both peoples overwhelmingly wanted their own state and were not prepared to settle for anything less. I could not see — and still cannot see — any other way of accommodating and reconciling these common, basic, minimum, irreducible aspirations, even if there are more formidable obstacles today in the way of their joint fruition than in the early 1970s.

Following years of agonized internal debate, the PLO eventually caught up with this harsh reality, grasped the nettle and formally adopted the two-state paradigm at its momentous Algiers congress in 1988. The immensity of this move should not be underestimated. It was a hard pill to swallow — and still today not everyone has fully digested it — as it meant lowering Palestinian sights from the hitherto immutable demand for 100 per cent of the land and accepting a scaled-down state on the remaining 22 per cent, comprising the occupied territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, with East Jerusalem as its capital. The implicit PLO recognition of Israel — and, by extension, West Jerusalem as its capital — became explicit and official five years later under the Oslo accords.

This was the Palestinians’ once-and-for-all grand historical compromise — although subsequently they went further still in agreeing in principle to minor, equitable land exchanges, provided that the 78:22 ratio was maintained and that Jerusalem would be the shared capital.

The evident belief of many Israeli leaders that a further deal may be cut over the residual 22 per cent — what Israel’s government, uniquely, calls the ‘disputed’ territories -– has been at the heart of the collapse of most peace plans to date. I do not suggest this was the sole cause of breakdown, for the remarkably low levels of empathy is a two-way street. But what has long been clear is that any future peace initiative would suffer the same fate as its predecessors unless Israel and its supporters were also ready to grasp the same decisive nettle.

Alas, there is no evidence of this on the part of the current Israeli government. Instead, many of its leading figures seem content, if not intent, on continuing the occupation of another people indefinitely and encroaching ever further on their land. Even many of the dissenters in Israel seem reluctantly resigned to this. Yet, if there is one cast-iron law of history, it is probably that occupations – which tend to brutalize the occupier as well as the occupied – and other forms of colonial rule are, sooner or later, resisted.

If Israel continues to deny the Palestinian people the freedom, independence and self-determination that its own people have enjoyed for the past 65 years, it can only be a matter of time until things turn nasty — and probably violent — again: a third intifada but, this time, possibly in the form of a vigorous secessionist movement in the West Bank. To put it another way, I fear the most likely alternative to two states by consensus is two states by chaos.

It is easy to hold that the current Israeli-Palestinian talks are headed for the rocks. Who among us hasn’t confidently predicted this? But before we succumb to the temptation of throwing up our hands in total despair — or kidding ourselves that a harmonious one state alternative is waiting eagerly in the wings — there may be a way to radically change the odds on the outcome of the talks. For, ultimately, the best way to heal the wounds of history is to ensure that the future guarantees everyone a decent place in the sun. Everything hinges at this time on making the failure of the negotiations prohibitively costly and success hugely alluring.

Here is where outside parties – such as the EU and the UK and other governments — could step in decisively and give themselves an effective seat at the talks. The virtual presence of other powers around the negotiating table, apart from the US sponsor, is vital in the light of the profound imbalance of power between the two main parties. It is no secret that some external actors are gearing up to take punitive measures, primarily against Israel, in the event of the talks collapsing.

Someone prominently involved in lobbying the EU on these matters sent me an email recently, in which she wrote: “I really do think that the EU is ready to become much more assertive in pushing for a just solution, although there will be a slight hiatus whilst Kerry runs its course”.

But why wait for Kerry to “run its course” before publicly advertizing these plans? What point is served by holding them in reserve as future retribution? Where will that get us, apart from further polarizing the situation? Would it not be more constructive and effective for outside parties to be fully open right away about their intentions, with the express purpose of influencing the course of the negotiations. Let the principal parties – and crucially their respective public opinions – know in advance what the price of failure, and the rewards of success, will be. A strategy such as this — which might well induce a necessary coalition reshuffle in Israel, if not a fresh election — may offer the only realistic chance of resolving the conflict without further bloodshed.

Practical and creative incentives and disincentives need to be devised for each party. The EU, for instance, could be very blunt about its immediate intention, should the talks fail, to implement scrupulously its recent funding directive that distinguishes sharply between Israel proper and its settlements in occupied Palestinian territory, and that other similar measures in the economic, travel and other arenas, are in the pipeline. Individual EU governments could issue matching pledges.

On the other side of the balance sheet, Arab heads of state could map out clearly what normal relations with Israel, as envisaged under the oft-repeated Arab Peace Initiative, will look like in full panoramic colour. They could add a pledge to pay official visits to Israel — as well as Palestine — as soon as a peace agreement is concluded. Other countries around the world could vow to move their embassies from Tel Aviv to the shared capital city of Jerusalem, to be accredited to both states.

Imagine the impact on both sides’ public opinion of an announcement that plans to hold a future Olympics or World Cup in Israel and Palestine were under serious consideration. That massive external investment would help build new cities, industry and transport systems in the new Palestinian state, opening both states to efficient trading and travel connections with the wider region. That boycotts and sieges on all sides would be lifted. That Israel in addition to Palestine would be invited to participate in regional cultural, sporting, trading and other agencies and, in parallel, were promised enhanced relations with the EU.

Such imaginings just scratch the surface. But they are not far-fetched. Before all the experts dismiss them out of hand, let them bear in mind the conundrum with which I started this talk. What is imagined now could conceivably be reality in the not-distant future. It depends on the decisions we choose to make. If every government, international agency and civil society thought deeply about what they could do to influence the outcome of the talks during these few months of enforced quietude, and set about doing it right away, the future may not be as grim as generally feared. It’s a rare, if unintended, opportunity that should be seized now. However, I expect, once again, for one convoluted reason or another, that it won’t be.

Well, I’m sure there is plenty there to disagree with. Thank you.

This is a transcript of the talk by Dr Tony Klug delivered at the Balfour Project Conference,‘Healing the wounds of history’, on 30 October 2013.